No matter how old I get – I will never forget an incident I experienced when I was just about eleven years old. I spent the summer holidays as a stable boy on the same farm, as I had done several times before. My main job – if you can call it that – was to provide the harvest workers with coffee, cakes and other provisions during the hay harvest.

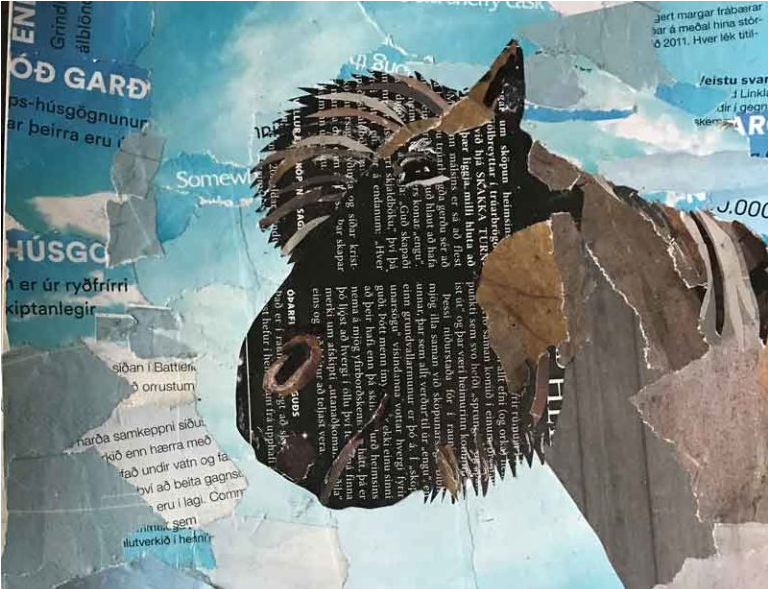

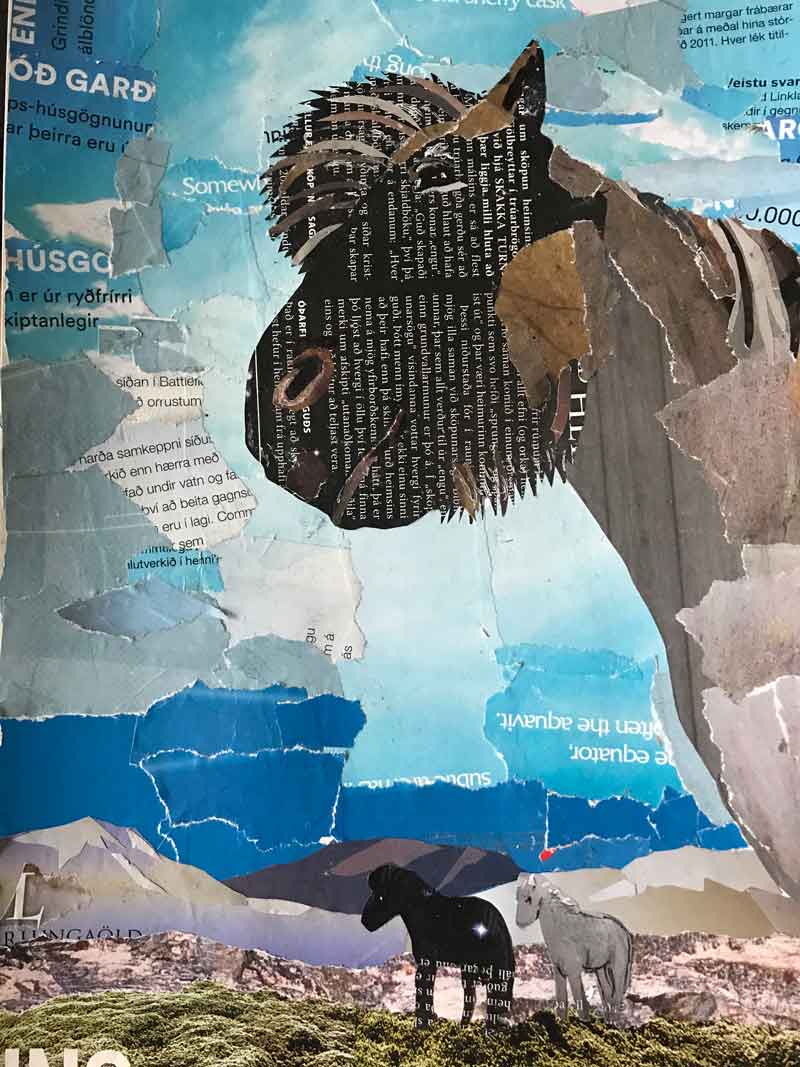

For this I always got the same horse, a sixteen-year-old blue dun gelding who was always simply called Mósi. Like many country boys, I only wanted to ride good horses.

But was Mósi a Gæðingur (Gæðingur= outstanding riding horse), some of you might ask. I could not judge that, as he was already at an advanced age when I met him. If I am not mistaken, he must have been fast and fearless when he was young. When I started riding him, he was already a little worn out and the youthful lightness had long since disappeared. However, he was always willing to work, easy to handle and very comfortable to sit on. He was also very well-behaved.

I owe a lot to Mósi. He was always the one who made the long walks easier for me and supported me in all the more difficult tasks. From my side, it would have been a breach of trust to say a single bad word now that he has died and our paths have long since parted for good.

Memories of old Mósi warm my thoughts not least because I can’t get it out of my head that I owe my life in part, if not entirely, to him. This is related to an event that happened during my work, which I mentioned at the beginning of this report.

It happened on a sunny day during the hay harvest. I had already done the chores assigned to me for the morning and ran to the pasture with a bridle in my hand to fetch Mósi, because it was time again to bring the harvest workers their lunch.

When I arrived at Mósi’s, he looked at me as if to say, “Oh, is it that time again?” But as always, he willingly let me lead him to the house. There I put the small saddle on him that I had been lent for the summer. The farmer’s wife came with the provisions I was supposed to bring to the harvest workers. It was a rather large bucket with drinks and a sack full of flat bread. I tied the sack to the girth and after I was seated in the saddle, the farmer’s wife handed me up the bucket, which I had to carry in front of my lap. When I had balanced myself and my luggage in the saddle, Mósi slowly walked down the path towards the mowing meadows at the edge of the mountain.

To get there, one had to ride criss-cross through deep gorges and crevices. The narrow paths were only rudimentary. It took about an hour at a walk to reach them. However, there was another way to the mowing meadows that was much shorter.

This was below the ravines and led through a wet moorland with many small ponds and bog holes. However, the farmer had strictly forbidden me to take this path, as it could be dangerous for me and the horse. Until that day, I had always followed his instructions and taken the paths at the edge of the mountain. Today, however, as I had just ridden away from the farm, I had the idea that it might be more fun to ride the lower trail.

Perhaps it also played a role that the farmer had scolded me the day before because I had brought the food too late, although it was not my fault. I didn’t want it to happen a second time and probably decided to take the shorter route for that reason. I also knew that at the end of the path you could make a detour towards the mountain before being seen by the harvesters.

Then it would look like I had taken the usual route.

Alles ging recht gut und ich ließ Mósi weitgehend allein den Weg für uns wählen. Er mied alle nassen Moorsümpfe und versuchte die trockeneren Bereiche zu erwischen. Everything went quite well and I let Mósi choose the path for us largely on his own. He avoided all the wet bogs and tried to catch the drier areas. So he was pattering along the mounds and I had hope that everything would be all right. However, the worst area was still ahead of us. We had to fight our way below the gorge “Illagil” (name of a gorge in Iceland).

There, the moor swamps were the most dangerous and there was hardly any solid ground to be found. However, I could not turn back now and therefore left it entirely up to Mósi to decide where to put his footsteps. But suddenly he sank deep into the bog. It all happened so fast that I had no time to react. Because I hadn’t saddled up tight enough, I slid to the side and sank so deep into the mud that only my head was sticking out and I couldn’t move my hands or feet.

If Mósi had stomped around, I would have sunk even deeper and surely suffocated under the horse. It was as if Mósi suspected it, because he didn’t make the slightest movement. The two of us wouldn’t be able to stand it for long and would inevitably sink deeper and deeper if help didn’t come quickly. However, I did not even make an attempt to call for help: I was petrified and silent as the grave. It was as if someone was preventing me from calling out, even though we were close enough to the people and there was a chance that they would hear me and come to our aid.

At that moment, many thoughts flashed through my mind, but I could not sort them out. Strangely enough, I did not feel any fear, which amazes me to this day, because I actually had no hope that we could free ourselves from this bottomless swamp and it seemed that only death was waiting for us. The people were mowing west of the ravine that day and raking the hay. As there was a hill between the hayfield and us, the harvesters could not see us coming. But then a small mishap happened, which I still interpret today as a sign of an invisible force majeure.

One of the girls had broken her rake. The farmer took the pieces and walked with them to the tent, which was a little higher up the slope. From there, one could overlook part of the moorland. Tools and spare parts were stored in the tent. The farmer probably wanted to get a new rake. When he came out of the tent, he glanced over at the bog and saw Mósi stuck in the swamp.

He could not see me, which was not surprising, since only my head was still sticking out of the ground. The farmer called the harvesters to him and asked them to quickly follow with ropes. He himself ran to Mósi and me. I only noticed him when he was right in front of us. Basically, the farmer was a kind-hearted man, but he was temperamental and could become very biting and unpleasant in his choice of words. Even in this predicament, which was so unfortunate for me, he could not control himself and scolded me before setting about rescuing me.

He hurt me very much with his words and I found it inconsiderate and inappropriate to reprimand me in this emergency situation just because I had not quite followed his orders. Only after his punitive sermon did he begin to rescue me and finally succeeded, with great effort, in pulling me out of the swamp.

Meanwhile, Mósi remained completely motionless – even when the men put the ropes around him, he did not move. I have never seen an animal that remained so calm under such circumstances. But when the ropes tightened, he showed strength and speed and apparently fought his way out of the bog with little effort. Afterwards he shook himself and glared at the bog hole.

I don’t want to describe what I looked like after that mud bath. As for the provisions, the bucket and its contents disappeared into the swamp and never reappeared. The sack of flat bread attached to my belt was the only one that could be saved, but after the mud bath the bread was no longer very appetising. I never thanked the farmer for saving my life. I was probably too hurt by his sharp rebuke before he helped me out of my furtible situation.

But I remember very clearly that afterwards I went to Mósi, snuggled up to him, stroked him and thanked him. The horse had shown more consideration for me in this bad situation than the farmer! Mósi is only an animal, but he had sensed the danger and by keeping calm he contributed the most to our rescue, in my view. I don’t think I realised at the time how great the danger actually was, only later when the farm people talked about it.

In recent years, this incident has often crossed my mind and it made me think a lot of old Mósi. The memory of him warms my heart more than many other things I have experienced and I will never forget him, even though he has been dead for some time now.

The memory of him remains linked to the event described here. I will never forget how calm he remained and the wisdom he showed in this accident. In my eyes, he was my lifesaver and not the farmer, although ultimately it was he who pulled me out of the swamp. I also find it remarkable that the rake broke at the very moment that Mósi and I sank into the swamp.

If this had not happened, the farmer would not have made his way to the tent and probably we would have been discovered too late or not at all. I have therefore always had the feeling that a force majeure was at play at the time, a power that can control people’s destinies with invisible hands and through which paths open up that are incomprehensible to us.

Largó

Original title: Mósa minning. Dýraverndarinn, volume 1931, 8. issue, page 65-66.

The story has been translated from Icelandic as accurately as possible so as not to change its character.