The following story tells of how a man got into distress with his horse and at the last minute did not have to carry out the cruel decision he had felt obliged to make as an animal lover.

I had a chestnut roan as a riding horse for a long time. He came from southern Iceland (Öræfasveit) and had enjoyed a good upbringing. His name was Litfari. I got him in 1872, when he was five years old, and had to put him down in the autumn of 1885, as he became dyspneic at that time and I could not have looked after him as well as he deserved during the following winter.

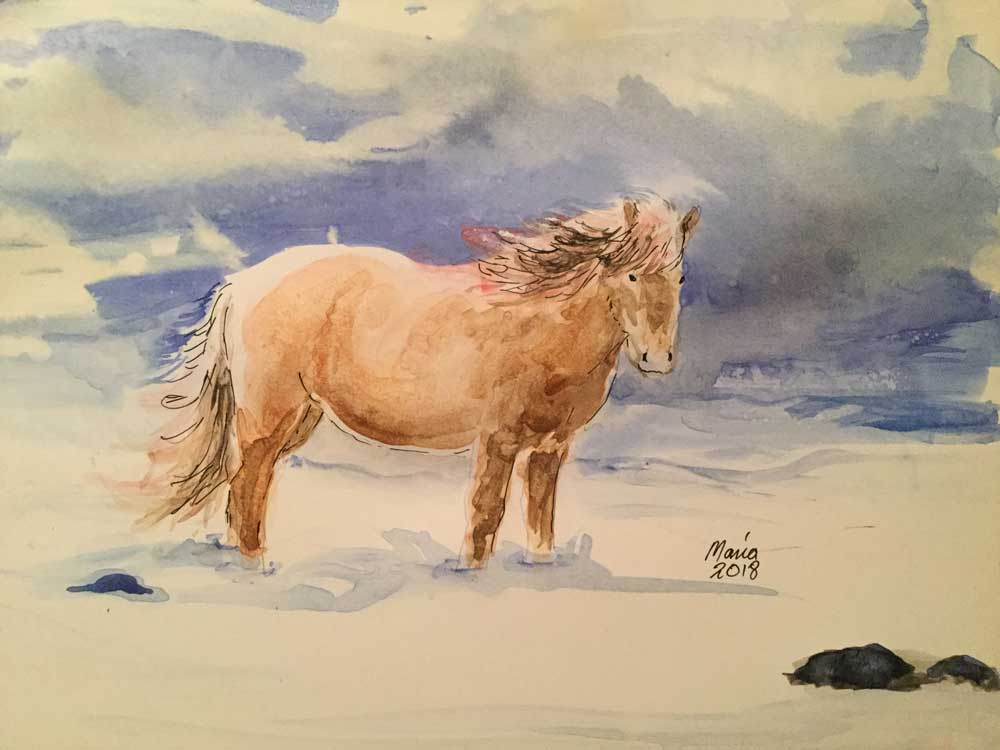

Litfari was of average size, somewhat strong and stable, but nicely built. Until his death, he had a good temperament without rushing forward, he was soft to sit and quite fast in pace. Above all, he was reliable, very sure-footed and a good swimmer.

He also had a “swimming vertebra” (Isl. sundfjöður) on both sides of his neck and a good sense of direction. That is why, as long as he lived, I never needed a guide when I was out on dark nights or in snow showers.

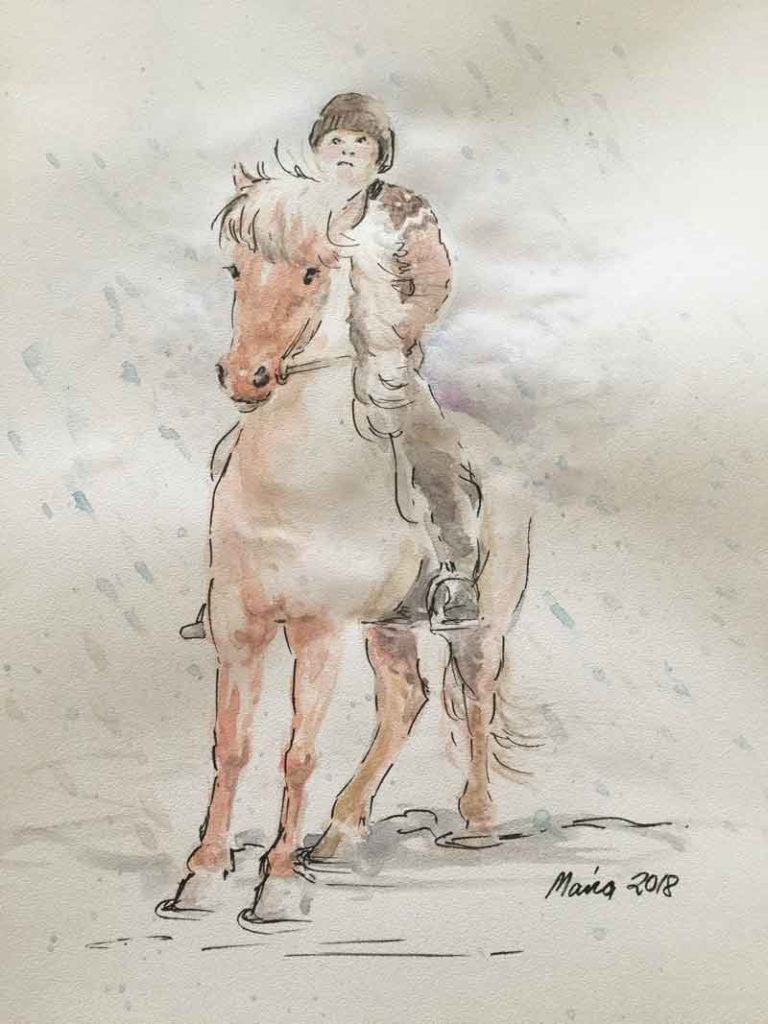

Once I was on my way home at night in a snowstorm. It was so dark that you could hardly see your hand in front of your eyes. But since relatively little snow had remained, I was able to ride home quite quickly. I hardly knew where I was when Litfari suddenly stopped and didn’t want to go any further, and this despite the fact that I drove him on without thinking.

But then I decided to let him take the reins and decide which way to go. He immediately turned around and ran directly into the snowdrift against the wind direction, until after a while he stopped directly in front of his stable door, where I normally always unsaddled.

This was not the first time he saved my life in snowstorms, darkness or crossing rivers by taking the lead.

Another time I was riding again in winter on my way home. It was quite cold, but the moon was shining brightly, so it was good to ride.

I was riding through a frozen bog when suddenly the ice broke under Litfari and he sank into a boggy swamp. Somehow I managed to separate from him, but he sank so deep that soon only his head was sticking out.

The bog hole was round and very narrow, also the opening was so badly frozen that I could hardly widen it. But with great difficulty I could at least cut the girth and remove the saddle.

I sat with Litfari for almost an hour, pulling the reins in all directions and tapping his mane with the whip to make him try to free himself, but to no avail. He did not move in the slightest.

It was a relatively long way to the next farm and although I was confident that I could find it, I did not expect to be successful, because I was not sure that I would be able to find the bog again with Litfari.

Therefore, I did not put any hope in the idea of saving him by trying to get help. But I did not want to leave my horse alive in the swamp under any circumstances, so that he would freeze to death in the icy cold.

Therefore, with a heavy heart, I decided to kill him with my pocket knife before I left him.

I always had a whetstone with me and started sharpening the knife. Every now and then I looked over at him. Litfari looked at me with the most pitiful look imaginable.

It seemed to me that he understood what I was trying to do. When I had sharpened the knife, I tried the reins one last time. And indeed, suddenly there was movement in him and he jumped out of the swamp, seemingly without much effort.

I think on our way home we were as fast as we have ever been before or since, but my friend needed to warm up as quickly as possible after this adventure.

Eggert Ó. Brím

Original title: Um „Litfara“ og „Löpp„, Dýravinurinn, 3. year 1889, 3. issue, page 30-31

The story has been translated from Icelandic as accurately as possible so as not to

change its character.