At the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th century, people’s attention was increasingly focused on the intelligence of animals. This was certainly connected, among other things, with the fact that the British natural scientist Charles Darwin had published some theses on this subject shortly before.

Wilhelm von Osten, a retired elementary school teacher, had set out to prove the horses’ ability to think. Unfortunately, his horse had died of intestinal entanglement before he had reached his goal.

A “new” Hans comes into play

But Mr. Osten did not give up. A few years later, he began looking for new ways to provide evidence of horses’ ability to think.

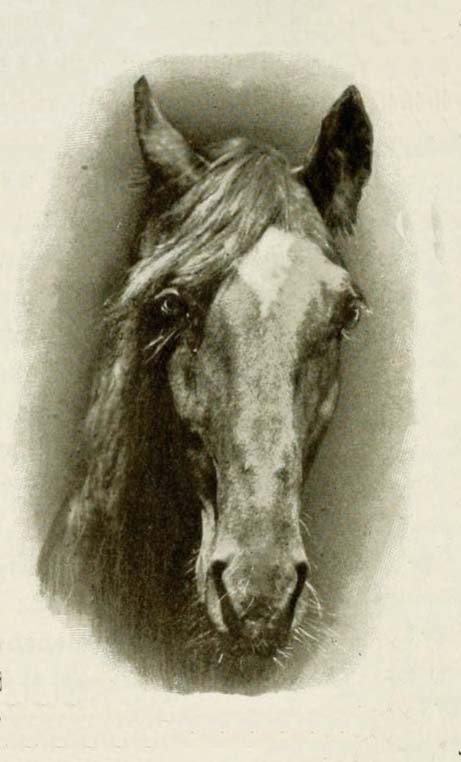

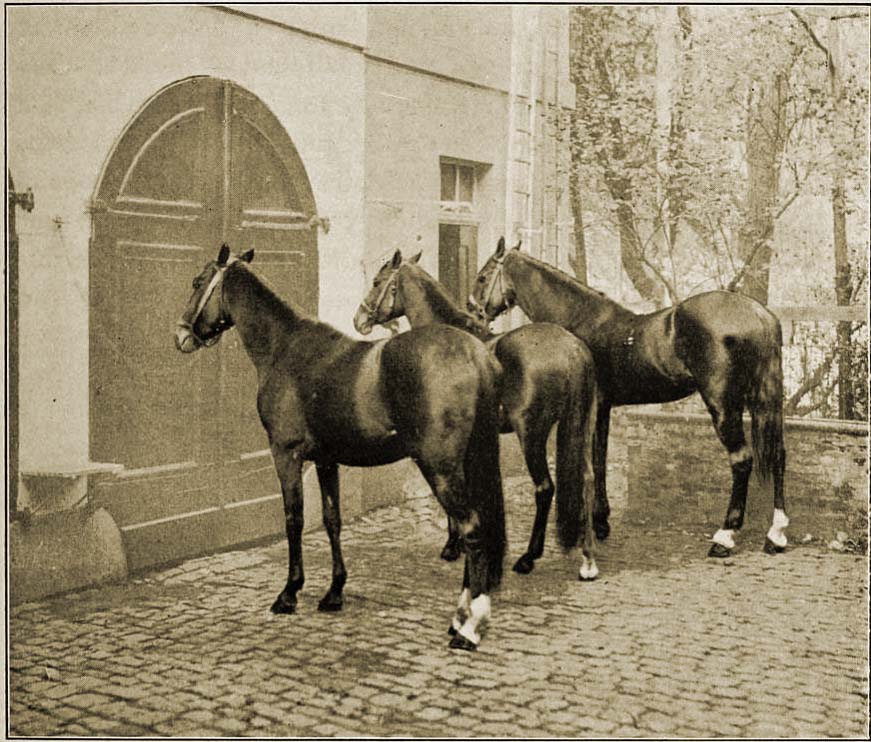

Therefore, he traveled to Russia in 1900 to select a suitable horse for his studies. He decided on a five-year-old Orlov trotter stallion, a black one with a star, and took him with him to Berlin. This horse was also named Hans after his predecessor.

In the meantime, von Osten was a pensioner and no longer had to teach math and art at the elementary school. He now finally had time to pursue his interests and could focus all his attention on a single pupil, the Orlow trotter Hans!

The four legged pupil

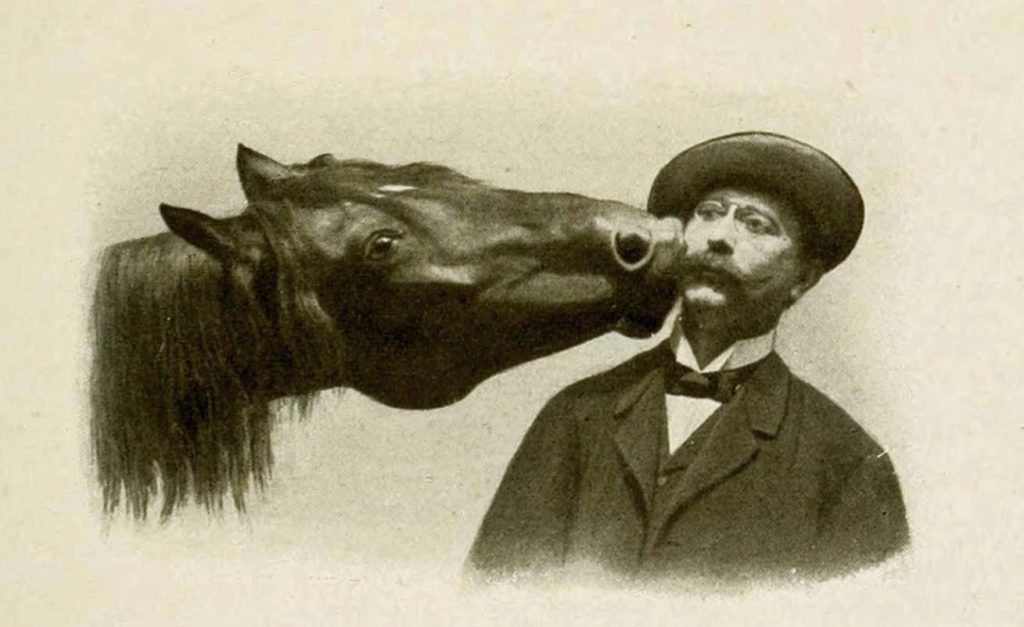

Von Osten quickly realized that the “new” Hans was not as sociable as his predecessor, but rather temperamental and moody. He was also extremely sensitive to external stimuli.

Nevertheless, he worked with him every day, usually for several hours and in all weathers, patiently teaching him all kinds of things, much more than what you normally teach your horse.

He worked out with Hans the difference between right and left, up and down, etc. But that was not enough for the ambitious teacher and so he began to teach his pupil how to count.

To do this, he used small hats, with the number of hats representing the corresponding number in each case.

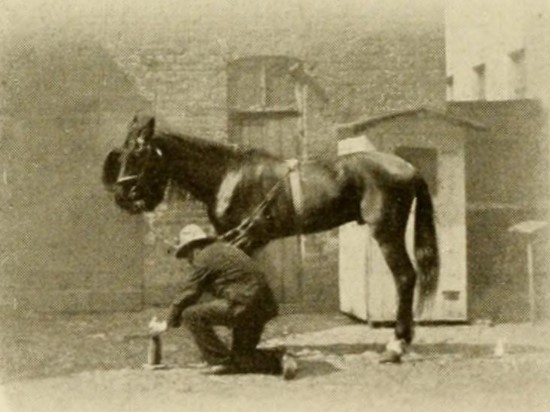

Each lesson began as follows:

Von Osten squatted next to the horse, lifted its right foot, pointed to the little hat and said “One” in a firm voice.

He repeated this procedure for hours. After a few weeks, the second step took place:

Now he gradually increased the number of little hats, naming the corresponding number each time. In a final step, he replaced the little hats with large metal numbers.

Mr. von Osten was rewarded for his efforts: After less than a year, Hans was able to indicate numbers up to 15 by scratching with his right front foot. The basis for teaching arithmetic was thus created and could be started.

Hans was a very good “student” and after only two years mastered all four basic arithmetic operations (addition, subtraction, multiplication and division).

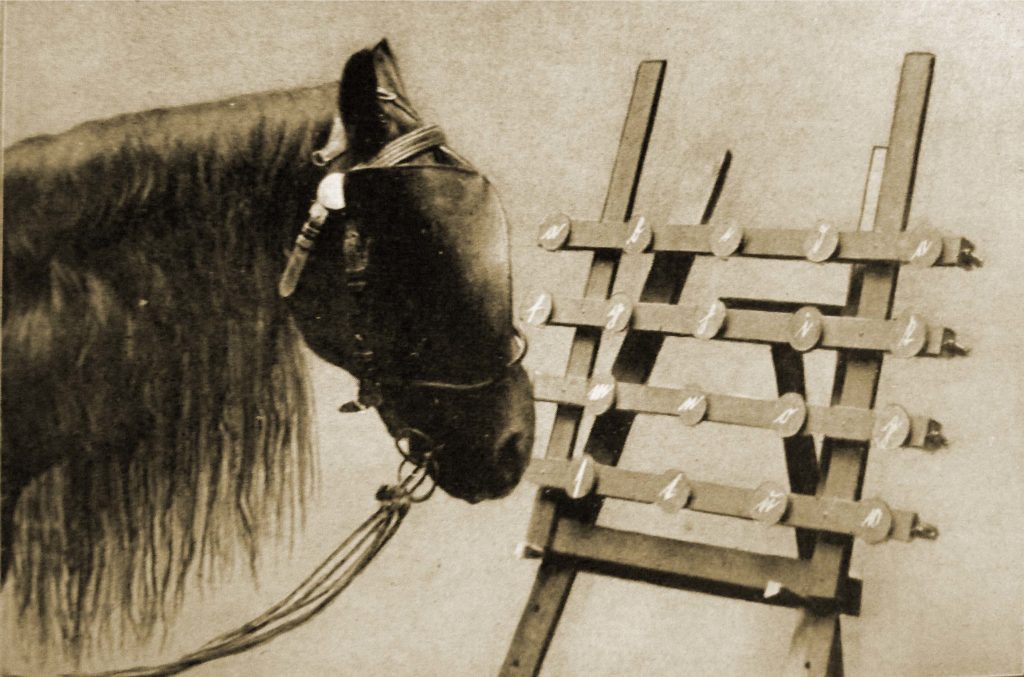

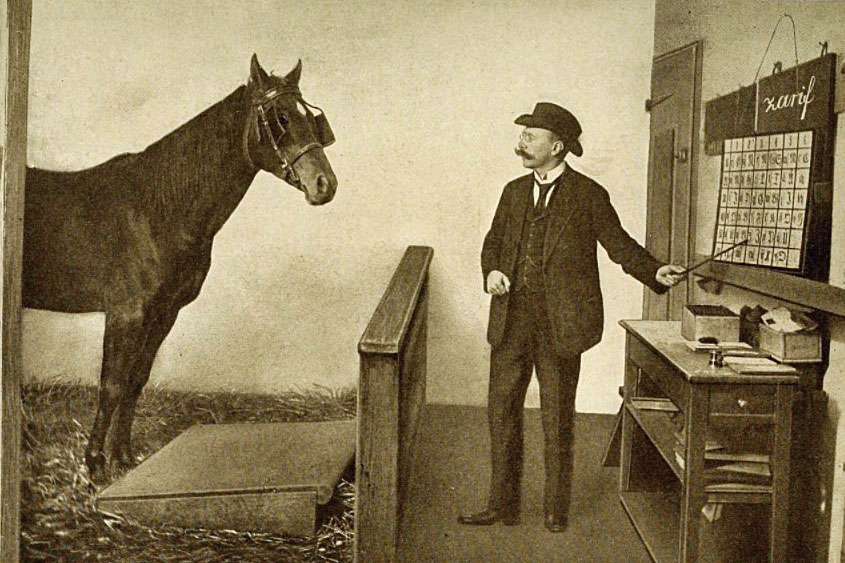

But not only that, Hans was soon able to spell and read words, recognize different colors, pick out individual notes of the musical scale, read the time and many other things that horses normally can’t do, not even circus horses!

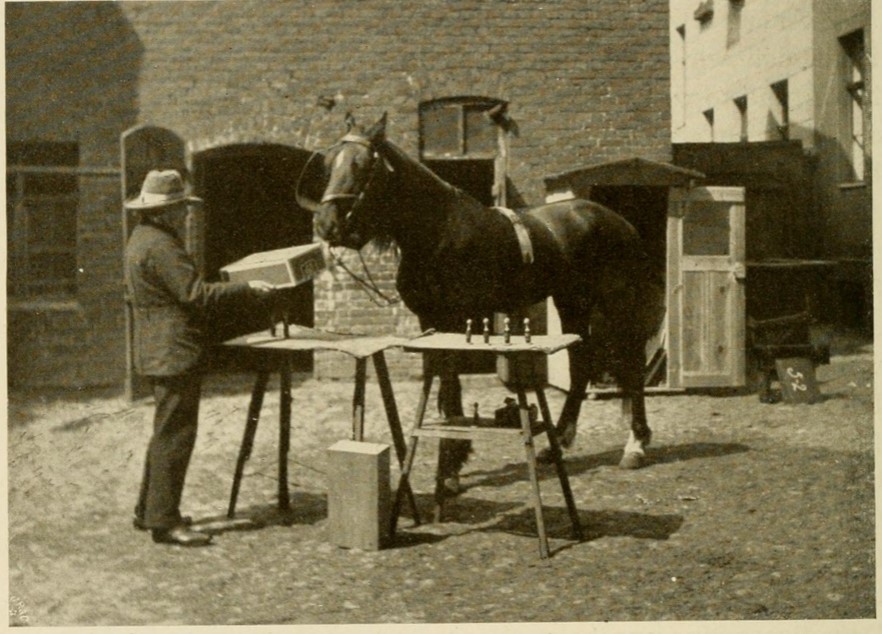

Part of the little hats was initially covered with a small box. When counting together, the emphasis was on AND. Then all the little hats were shown to the horse.

Mr. Osten brings Hans to the attention of the scientific community

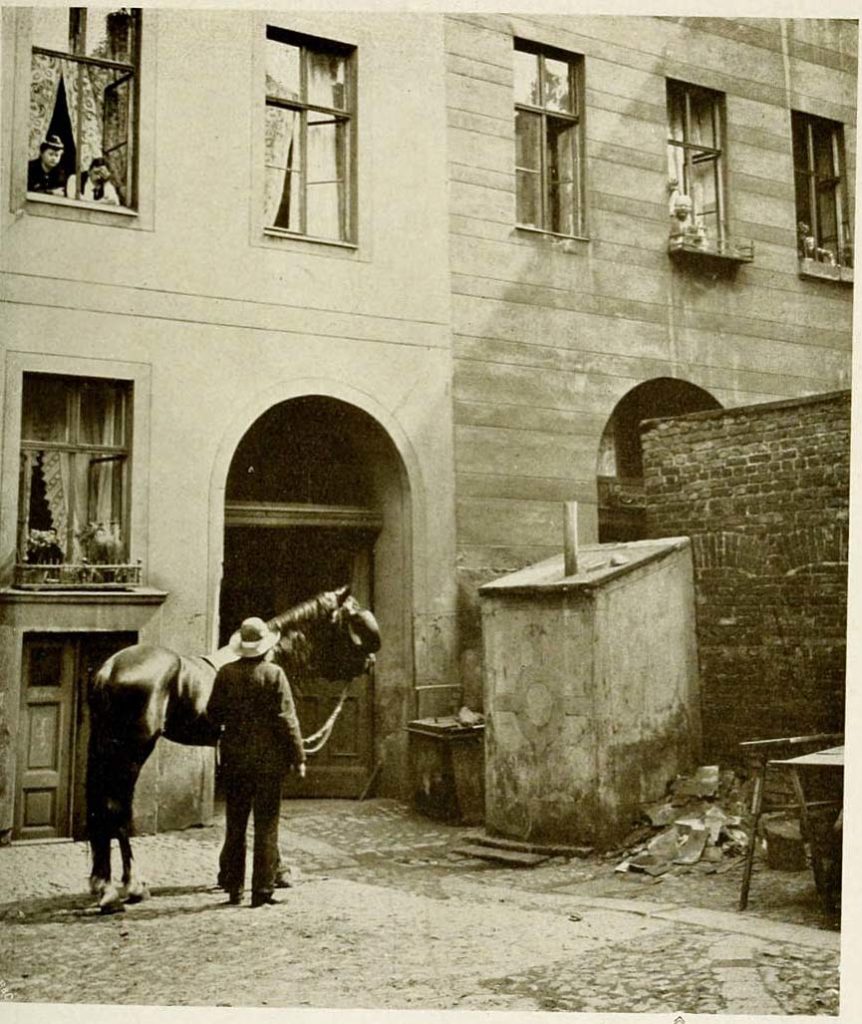

Now the time had come for Mr. Osten to show the world his horse’s ability to think. He sent letters to scientists in Berlin and the surrounding area, inviting them to observe Hans reading and calculating in his backyard. Understandably, he was not taken seriously and got no response to his invitation.

Mr. Osten did not intend to be discouraged by this and he looked for another way to draw attention to his intelligent horse. Next, he tried a sales ad in a daily newspaper with the following text:

“Stallion for sale that served as a test subject for my study on the thinking ability and intelligence of horses.

He is 7 years old, very well-behaved, can read and calculate, recognizes 10 different colors and can do much more!

Information from Mr. W. Osten, Griebenowstraße 10, Berlin.”

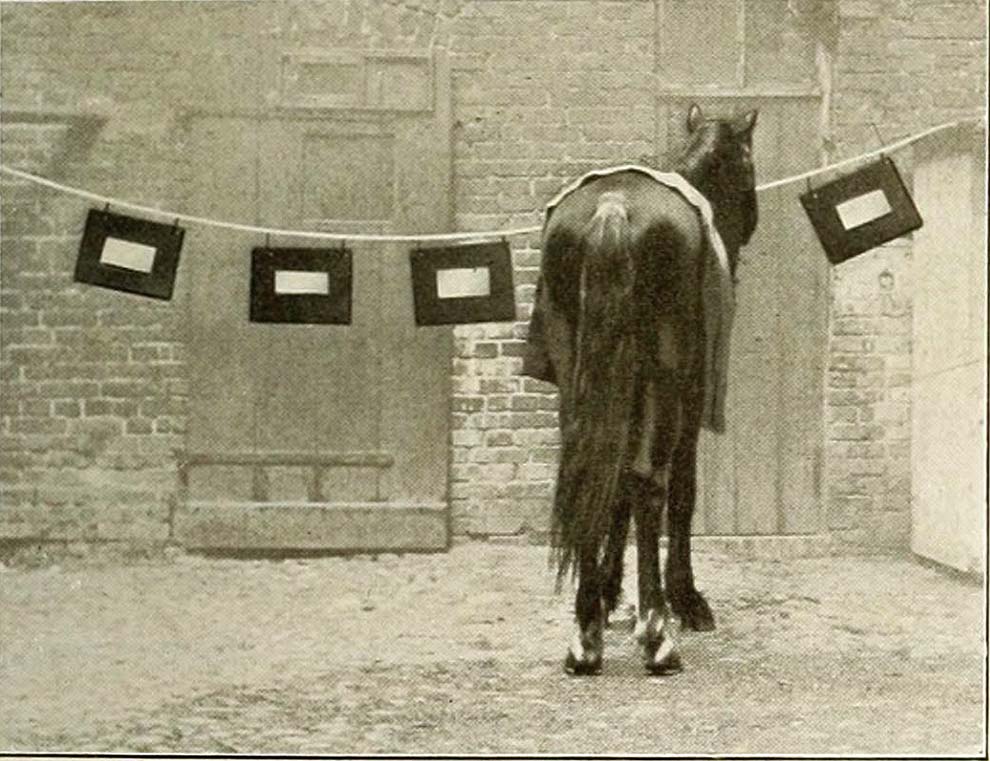

Hans stands in front of different colored color panels and touches the panel with the blue color with his nose.

Mr. Osten hoped that in this way he could arouse interest in his horse. However, the ad did not have the desired effect, but was rather perceived as a kind of April Fool’s joke. Once again, Mr. Osten changed his strategy and offered free demonstrations of the stallion in his backyard.

Now there was finally a ray of hope. An officer became aware of the display. He came to the demonstration and was very impressed by the horse’s ability. But that was not all: in August 1904, he wrote an enthusiastic article that was published in the daily newspaper Weltspiegel. There, he described how the horse “answered” all the questions he was asked, without his teacher having had the opportunity to help him.

Hans becomes famous and gets the nickname “Clever Hans”

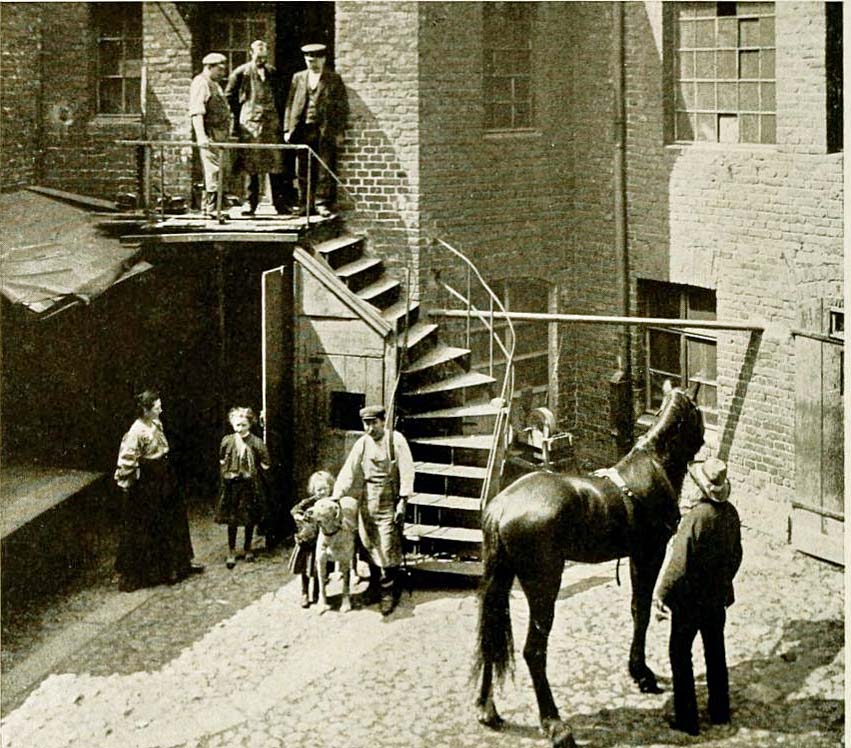

The article met with a great response and the thinking power of Hans the horse was suddenly on everyone’s lips. Articles about Clever Hans, as he was called from then on, appeared in the daily newspapers almost daily. In front of the residential building in Griebenowstraße, traffic chaos was now part of everyday life and the backyard was full of visitors who wanted to see the wonder horse.

In early September 1904, a major article about Clever Hans even appeared in America in the New York Times with the title:

“Berlin’s wonderful horse! He can do almost everything but talk”

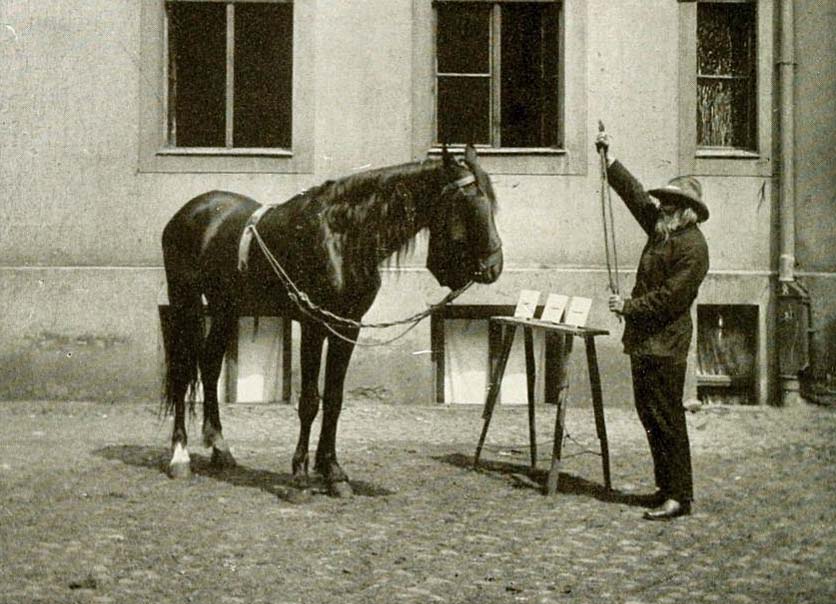

Half an hour later, the horse is asked to spell the name of the man with the nose with the help of the blackboard.

In the article, an eyewitness enthusiastically described how Hans distinguishes gold, silver and copper coins and recognizes their value, in addition to giving a sample of his mastery of fractions and even being able to recognize people from the audience or from photographs.

Even the Prussian Minister of Culture paid Hans a visit and was subsequently also convinced that Hans could solve the tasks without any tricks or signals from outside.

The September Commission

Now they wanted to know exactly! To make sure that there were really no tricks or secret signals involved, a commission of 13 experts was put together, consisting of psychologists, a veterinarian, a trainer, a biologist, horse trainers and other horse experts.

On two days the commission investigated Clever Hans thoroughly even in the absence of his teacher.

The scientists unanimously concluded that it was impossible that Mr. Osten had used signals or tricks while training Hans.

The guesswork about Hans’ abilities continues

However, after the commission’s announcement, the horse’s thinking ability continued to be controversial. Some now suspected that special abilities from the fields of occultism, suggestion, mind reading or transmission of will were involved.

Similar spectacular cases fueled the discussion and led to more and more investigations with Hans, e.g. the experiments with the dog Nora.

Its owner, a certain Emilio Rendich, had managed in a similar way as Mr. Osten to teach his animal to respond to questions – in this case with barking.

Rendich had watched von Osten’s lessons for weeks, practicing with his dog in a similar way until she could finally respond to questions as well.

The mystery is solved

But even this example could not dispel the doubts about the ability of animals to think and called for new scientific research. Now a team of psychologists took another close look at Clever Hans and announced the results of their investigations on December 9. It was:

The horse Clever Hans can neither read nor calculate!

This realization was very sobering, especially for the owner and teacher of the horse who could not be dissuaded by anything in the world from his opinion that his horse could think. But he was probably alone in this, because after the announcement of the latest results, it suddenly became quiet again in the Griebenowstraße. The audience had lost interest in Hans.

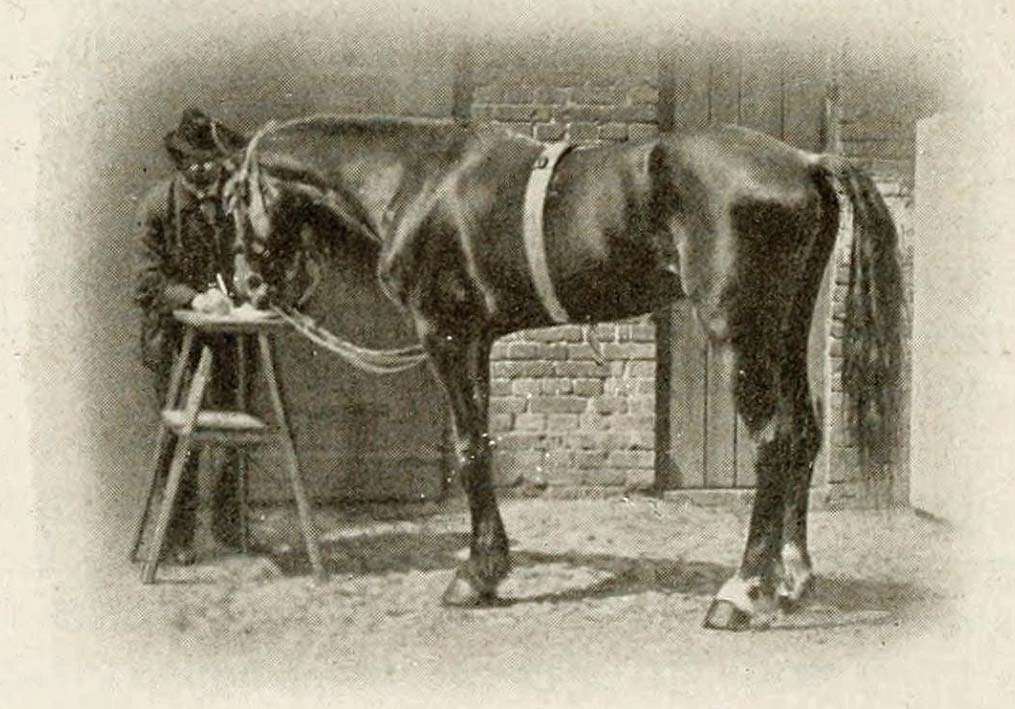

Photo/Karl Krall (1863-1929).

The Clever Hans Effect

But how had it been possible for the horse to answer numerous questions correctly, as confirmed by countless spectators, when it could not think? The scientists had found a convincing answer to this question:

An important part of their series of experiments had been to isolate the horse from its environment during questioning, even at times fitting it with blinkers to completely eliminate the possibility of visual cues. Furthermore, the horse was asked questions whose answers were not even known by the questioner himself. Under these conditions, the horse failed.

The psychologists interpreted the result of their experiments as follows: The horse had learned to pay attention to the smallest, perhaps even unconscious, changes in the questioner’s posture and to take a hint from this for the answer.

The scientists suspected that the questioners had unconsciously assumed a tense body posture when asking questions which had been relieved by relaxation when the horse gave the correct answer.

Mr. Osten continued to teach the horse Hans for a few years until he himself became seriously ill.

The animal, they suspected, had not thought for itself, but had reacted to these body language signals. It was driven by the prospect of a reward in the form of a piece of bread or a carrot.

These findings have gone down in the history of science and helped experimental psychology and animal psychology to make a breakthrough.

A shattering result

After the riddle was solved, it became quiet around Clever Hans. But his owner continued to teach him. Stubbornly, he stuck to his life’s work of convincing the public of his horse’s ability to think.

He even considered selling Clever Hans abroad, or even giving him away, if he were given the recognition he deserved there.

But before this could happen, Mr. Osten fell ill with liver cancer and died in June 1909. Until his death, he was convinced of his horse Hans’ ability to think.

He blamed his failures on the horse’s capriciousness and his illness, which had prevented him from convincing the world of his horse’s abilities through new results.

In 1909 after the death of Mr. Osten, CleverHans has become the property of Mr. Karl Krall.

What happened next with Clever Hans?

On his deathbed, Mr. Osten decreed that Hans should become the property of Mr. Krall. Thus, shortly after his death, the horse was transported to Elberfeld in Westphalia, where his new owner carried out further experiments with him and some other horses at his “experimental station”.

In 1912, Karl Krall published his book with detailed descriptions of the series of experiments that he himself and Mr. von Osten before him had conducted.

He formulated his motivation for this book as follows:

“My attempts at teaching with my own horses were made to save Mr. Osten’s discovery from demise.”

Karl Krall, Denkende Tiere, Leipzig 1912, page 243

Because Mr. Osten himself never wrote down or published anything about his experiments. He had not even demanded entrance fees for his demonstrations with Hans.

Despite an investigation period of seventeen years in total, even Krall could not convince the world of the horses’ ability to think. But the experiments were nevertheless of value: they helped to make decisive discoveries in experimental psychology and animal psychology.

In 1916, all horses in Krall’s possession were drafted for the war. This also applied to Clever Hans, who was allowed to enjoy at least a few more years of retirement with his new owner beforehand.

His further fate is unknown!

- Karl Krall, Denkende Tiere, Leipzig 1912

- Oskar Pfungst, Das Pferd des Herrn von Osten (Der kluge Hans). Ein Beitrag zur experimentellen Tier- und Menschen Psychologie, Leipzig 1907

- www.wikipedia.org

- Photos from the book after Karl Krall, Denkende Tiere, Leipzig 1912